skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Ash Wednesday is just around the corner making this the Sunday before Lent. We continue with Christ’s Sermon on the Plain. Last week, love was in the air but Christ did not propose a plasticky passion promoted by popular philosophy plumped on a diet of feelings and personal fulfilment. Instead love for Christ was made clear on Calvary: “Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing”.

Today, Jesus specifies how that same love is to be lived. A good point of entry is judging others. “Do not judge. Take the plank out of your eye before attempting to remove the splinter from your brother’s eye”. This instruction is a powerful club that is often wielded to “silence conversion” and not just conversation. Just the accusation “You are judgemental” is enough to stop people in the tracks. Tell me you do not fear this label that oozes self-righteousness?[1]

What does it mean that we are not to judge? This would be true if one’s attitude is “I am better than you”. But if one’s approach is the spiritual well-being of others, that would be different because admonition is a spiritual work of mercy. To check or counsel is not setting oneself up as judge but it is an action that comes from a space where the relationship is marked by love and caring. Trouble arises when smug sanctimony is dressed up as love for the spiritual well-being of others. We can be blind to our holier-than-thou attitude. The older we are, the more judge we tend to be.

We must not be sanctimonious but judge we must. Jesus called the religious leaders of His time, “brood of vipers”. If that is not a unflattering judgement, what is it? However, His assessment when dealing with situations of sin gives us a clue on how we ought to proceed. To the Woman at the Well He showed mercy, and like the Woman caught in Adultery, sent her off reminding her to sin no more, demonstrating that true judgement is rooted in charity. He judged because there are morals attached to our relationships.

In a sense, we might as well be “judgemental”. This mindset does not refer to a wilfulness in which we set out to be obnoxiously so. Rather, it comes “naturally” when the “world” lowers its standard. In other words, Christ’s teachings have not changed. Society has. And as it does, it expects everybody to jump on board with the accepted norms and the Catholic Church is not exempt from this pressure to fall in line with the latest trend or newest narrative.

Think of society’s positions towards premarital sex, divorce and contraception. These were once taboo in all Christian denominations. When the Pill was discovered, it changed the landscape of freedom. The body, once upon a time, was sacred ground for the purpose of procreation is now inebriated with the nectar of abandonment and is transformed into the playground of recreation. Sex no longer serves a sacred purpose but has become a slave of pleasure. Even Catholics are overwhelmed by carnal decadence that we can no longer recognise the difference between purpose and pleasure.

What is the difference between Mrs Wallis Simpson or the Duchess of Windsor and Mrs Camilla Parker Bowles, aka Duchess of Cornwall? Both are divorcees. One could not become a Queen consort. The other will become one upon the demise of HM QEII. That is how much our attitude towards divorce has changed.

The Church continues to embrace the sacred truth about the human body and its place in the schema of salvation. The world cannot tolerate such dissent. As long as the Church holds onto the sanctity of marriage and family life, she is already on collision course with the current thought police. Our position makes us judgemental. To illustrate, we think that the Church’s position on divorce comes from Sacred Scripture. But it is also based on our understanding of God who is forever faithful. How do we know that? The only human reality that is capable of symbolising God’s steadfastness is marriage. Marital covenant between a man and a woman symbolises God’s faithfulness to humanity and Christ’s fidelity to the Church.

Christ is always faithful and nothing can come between God’s love for us and Christ’s devotion to His Church. If people make mistakes, why does the Catholic Church not allow for divorce? Is that not cruel? The nature of iconic representation is that the allowance for divorce is at the same time a statement that our God is not that faithful after all, which is never the case. Along the same line, why do we frown upon premarital sex? As the argument goes, what is wrong when the couple loves each other? Again we revert to the institute of marriage as a sacrament. As a sign, marriage symbolises Christ’s love for the Church, which means premarital sex becomes a lie. The couple is not married and they do not stand in for Christ and His Church. There is no representation and therefore, premarital sex is akin to asking heaven to witness to a lie.

When society lowers its morals, we will always be deemed as “judgemental”. In the last two or three decades, we have taken a deserved beating with regard to the reality that we have not lived up to the standards we expected of the world. Our failure is indeed our shame but our failures do not negate the truth on which the teachings of the Church stand.[2] Her sons and daughters may fail but Holy Mother Church must declare what is true, whether society approves it or not, and whether we ourselves can stand up to scrutiny. Judgement on the morality of a conduct or action should never be based on one’s personal merit or failure in behaviour thereof. Credibility or the integrity of the one who judges is a good thing but it can also be crippling because what this means is that as long as one is failing, one does not have a right to speak. The result is that one must not take a stand. In which case, nothing is ever wrong because everyone is failing!!

While it may be true from the perspective of hypocrisy that one should speak with credibility. Still it does not address the issue that there is an objective standard to judge a behaviour regardless of one’s personal failure.

Last Sunday, a point was made that we can trust God even though we may be wrongly judged. That despite how others may unfairly assessed us, we have to worry only of the judgement of God. This faith that grants peace and serenity in the face of injustice is based on a view of life that stretches into eternity. The same eternity is the reason for the courage to take a stand because everything that Jesus condemns or what the Church prohibits is based on that.

We resolutely make a stand even if that may come across as judgemental because society is confused and conflicted in the areas of personal morality, common decency and also right doctrine. We should rescue the scriptural instruction not to judge from the timidity of being labelled as self-righteous and restore it to the rightful place of charity and desiring the spiritual good of the other. We do not judge because we are better than others or take a stand because we are holier than thou but because we care about the eternal fate of souls. This conforms with the supreme law of the Church that is the salvation of souls (Lex suprema salus animarum). We judge now or take a stand because one day we will have to give an account of our life before the Judgement Seat of Christ.

__________

[1] This dogmatic sticker can easily be tagged unto Catholics. It is ironical that society is quick to perceive and be offended by racism, sexism, orientation. Yet, the very same victimised society has no problem condemning the Catholic Church as judgemental.

[2] The failure of the messenger does not invalidate the message. The lapse of the individual does not render truth any less true. Just because I failed to live up to God’s commandments does not mean that the commandments are useless.

We continue with Jesus’ teaching from last Sunday. From blessings and woes, we delve deeper into the heart of Jesus’ teaching—He establishes a new law to shape the new person. The mould of this re-creation is found in the 2nd Reading where St Paul speaks of Jesus Christ as the New Adam.

This new covenant is grounded on love. But what is love? Our definition of love is pretty much clouded by emotions. Our idea of love is rather permissive and it may have lost its meaning. Hence, to appreciate the commandment of Christ, we need to situate it within the context of being hurt or humiliated, maligned or mistreated, robbed or raped and the list goes on. Our reaction towards a person who has hurt us is almost always visceral. Deep within our being there is revulsion and a perception that whatever wrong had been committed cannot be forgiven. Therefore, love your enemy is not easy in any of these contexts. Do we want to return blessing for a curse? Or turn our cheek when we are slapped? Or give even if we know the recipient is cheating us? Perhaps, these are rather extreme examples. What about queue-cutters who drive up to the front of the jam and then cut into your lane?

Where the situation is clearly biased, unjust or unfair, do we retaliate and get even? Or do we give in and run away? Are these the only options available to us? On the one hand, getting even or reacting along the line of "lex talionis" may escalate an already bad situation resulting in further destruction to everyone involved. On the other hand, running away will only fester resentment and for some, they tend to take out their frustration on other, especially those weaker than them. This is more common than we realise. For example, spouses are known to withhold their affection or snap at their loved ones because they bring home their anger at work.

We realise that both these options, either revenge or retreat, do not assuage or appease the unpleasantness experienced from the original offence. In other words, we are left feeling empty. Revenge may appear sweet prior to its execution but once we have exacted it, we are left to deal with the sour taste of a wound unhealed. If not, we quietly recede from the scene. With exaggerated autonomy, we picture ourselves as self-made. As a result, this self-definition will certainly chafe at any perceived injustice. The earlier example of letting in a queue-cutter surely sends the wrong message that we are weak or we can be walked over. In short, we are losers.

The option proposed by Christ does not solve the problem of incompleteness. However it does allow us to take a longer look. At the heart of Christ’s teaching, the question must be asked: “How far does eternity go for us”? In an age of disbelief[1], not unbelief, we struggle to believe in the Resurrection. It is difficult to conceive that there is life after death. The miracle of the raising of Lazarus provides an insight into what death truly is and its place in our lives. In this familiar story, the Lord was 3 days late. But, say if the Lord managed to heal Lazarus before he died, what would the implication be? The cure did not mean that Lazarus would not die. A cure is merely a deferment of death, putting it off until a later time which implies that whatever we may do to stave it off, one day we will die. Death is the necessary door that opens us to the Resurrection.

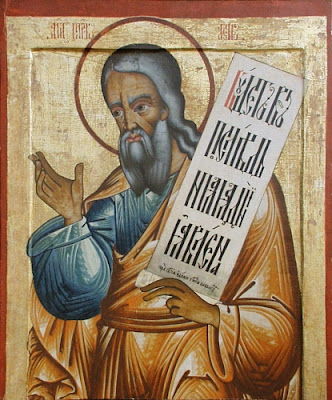

Isaiah the prophet never preached about the Resurrection but he might as well did so. He said that authentic justice and salvation are found in God alone. This is not an abdication of our duty to seek legal redress or look for a solution. What the Prophet simply affirmed was the unpalatable truth and a sobering reminder that on this side of death we are not guaranteed full resolution and satisfaction for our efforts in trying to right the wrongs. Therefore, the ability to stand apart from either revenge or retreat requires a firm belief in the Resurrection.

Faith in the Resurrection allows us to put up with the dissatisfaction of an unresolved hurt or the emptiness brought about by an untimely demise. More importantly, it gives us strength to love. For love is a matter of willing and it follows that there will be sacrifice when love is true. If it were just mainly emotion, then decisions taken will depend on how we feel. True love goes beyond how one feels. A good example is a parent who despite his or her illness, gets up in the morning and goes about the duties. Love pushes a person to be greater and better than he or she is

However, for that sacrificial love to go further it needs an assurance. Without the certainty of faith that God is just and merciful, if not in this world, then in the next, we will always be sickened by glaring gross injustice. We will find ourselves loving reluctantly or resentfully. Sadly, our therapeutic society seeks to solve all problems before death. When we are unable to find justice, we either flare up in anger or we withdraw into despair in the face of flagrant disregard for the simple demand of decency.[2]

The love which Christ invites us to embrace does not exclude “therapy”. It is not a fatalistic resignation. Maybe our notion of love is more selfish than selfless love. Nevertheless, self-love is important in the commandment proposed by Christ. One cannot give when one is empty. Thus, self-care is part and parcel of self-love. To be present to others, to give to others, to serve others, we need a little bit of space for ourselves. Jesus Himself stole away from the pressing crowd in order to be available to their incessant demands. We receive from God in order to give. That is basic to the Christian vocation.

Jesus’ teaching can either be painful or liberating. We may be sons of Adam, but through Baptism, we have become the brothers and sisters of the new or second Adam, Jesus Christ. Humanly, the ideal given by Jesus is hard to live by. But since Christ gave it as man, He must know that it is possible for man to live it. He showed it on Calvary. Jesus calls us to a love which He Himself has embraced. “Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing”.

__________

[1] Disbelief shows an unwillingness, unpreparedness or an inability to believe. Unbelief concerns the absence or rejection of belief.

[2] Even though right is right and wrong is wrong and at the very least what is right should be rewarded and what is wrong should be punished, our political geography provides ample instances where what is right is ignored and those in the wrong unpunished. We have just read that Prince Andrew or Mr Andrew Windsor has settled out of court with Virginia Guiffre, the woman who accused him of abusing her. Whether he did it or not is not important except that we are left with a distinct impression that the best ride in the game of life is not the roller coaster but the gravy train. Our woke justice is tainted by money!

As this current health crisis drags on, there is anxious yearning for a revival of a moribund economy. To spur the recovery, we are hoping for an accelerated easing of the various restrictions. Coincidentally, we are in the midst of the Lunar New Year. It is a season steeped with blessings because it is premised on the idea that the “xīnnián” should usher in abundance and prosperity. How much more good fortune than to wish someone “Gōngxĭ fācái”? Fortuitously, we have a chance this Sunday to dwell on the Christian notion of blessing. Is it just bounty and plenty or is there more to it than accumulation, achievement and accomplishment?

The 1st Reading gives a taste of what blessing should be and it is not linked to abundance. Instead, geopolitical considerations played a role in Jeremiah’s harsh and forbidding language. Between the Southern Kingdom of Judah and the Northern Kingdom of Israel, Judah was economically the poorer of the two. As the less developed of the two nations, Judah was fearful of the future as the Assyrians, Eygptians, and Chaldeans grew more menacing. Instead of humility, repentance and trusting in God, they disregarded the Lord’s commandments and the result of their disobedience was disastrous. In other words, Judah wanted protection from a greater power and hoped to achieve it through the formation of alliances with others. Whereas Jeremiah counselled the King against placing faith in human agency, he urged Judah to trust in God who has never failed to provide.

It has been the coherent counsel of the long line of prophets that we should trust God’s providence. This begs the question in whom we place our trust. Blessing flows from trusting that God alone will protect and provide. In fact, Jesus in the Gospel seems to suggest that God’s favour is almost non-material. In teaching the crowd, He addressed His disciples directly indicating that He expected those who follow Him to utterly abandon themselves to the God who is providentially faithful.

In the Beatitudes, Jesus describes how blessings and woes are applied to different people. The poor, the hungry, the mourners, the hated are blessed whereas the rich, the full, the happy and the popular have had their rewards. The woes which are directed to those who are creaturely comfortable—enough to eat, drink and enjoy—can lead to a hasty or unfair condemnation of those who are materially more well-off. In this age of glaring disparity between the elite and the marginalised, where the “equality of outcome”[1] becomes a burning issue for social justice, the elite are easily demonised as the “bête noire” of socialism.[2]

Inequality aside, what is evident in the Beatitudes is that plenitude is not the measure for God’s blessing. There is relationality in blessing and it would be myopic to restrict the notion blessing to the merely material realm. Thus, in the context of the Lunar New Year and our captivation with prosperity and wealth, it would be good to deepen our understanding of blessing.

Firstly, in proposing the Beatitudes, we are encouraged to embrace good and proper behaviour. It is an exhortation to be the best of who we are—an encouragement to virtuous and ethical conduct.[3] Good and proper behaviour is essentially relational in nature. Thus, the Beatitudes are a blueprint for righteous relationships.

Secondly, the idea of justice inherent in the Beatitudes is fruit of our faith in God. Justice will never be achieved if we place our trust in material well-being. We delude ourselves thinking that only when we have “enough” will we begin share with others. It is akin to the proverbial receding horizon. The more we accrue, the more we tend to hoard. Only when we are able to peer beyond the veil of material fulfilment that we will begin to appreciate the blessedness of poverty or deprivation. This is not a glorification of abject poverty because for some people, a meal is that thin line between life and death. The context for the blessedness of nothingness is found beyond having enough to eat, drink and enjoy. When we transcend this insatiable drive to accumulate and to hoard materially, we begin to treasure that the vacuum does not annihilates us. Instead, this gaping hole of incompleteness which often compels the need to acquire is the original emptiness placed there by God Himself. He is the only possession that can fully satisfy us.

Thirdly, if God alone suffices, then we will have to disabuse ourselves of the idea that blessing is a sign of God’s favour. It is not always the case. Some of us hold a perspective that blessing is synonymous with wealth. Take for instance “fú, lù, shòu” (福祿壽) otherwise known as the gods of fortune, prosperity and longevity. They reveal that our concept of blessing glides along a material plane. If not, look out for the “rotund cat with the forearm waving”, the Japanese “maneki-neko”, prevalent in Chinese and Catholic homes which beckons wealth and good fortune.

When we are focused on material plenitude, we may fail to appreciate the true nature of blessing. So often we forget that the Devil can bless too. Remember how Satan brought Jesus to the top of the mountain? There, Satan tempted Jesus to bow down and worship him. For that Jesus would be rewarded with the Kingdoms of the world. Jesus reminded Satan that authentic blessing flows from an authentic relationship with God. Plenty and abundance are not always signs of God’s favour for if they were, imagine how blessed Najib, Rosmah and all their corrupt cronies are.

It does not mean that we should stop asking God for His blessings. We dare to ask because it is an expression of our dependence on Him and yet we also know that the relationship between us should never be defined materially. If blessing equals wealth, then our relationship is not with God but with His creation of which God is simply the vending machine that provides all these. Blessing flows when we trust in God but it does not have to be material. If God does not answer our prayers, it is not because He condemns us.

Finally, blessed are the poor could well be a definition of an attitude and not a description of deprivation. Happy are those who have a relationship with the Lord for their lot or portion will be overflowing! Sad are those whose faith is not in God, but instead in their own machination, believing that wealth, prosperity and fortune are enough for life. In this unequal society, to address injustice or the skewed distribution of wealth, we need to tackle first this central issue that blinds us from recognising that the basic equation of life is our relationship with God[4] and only then, with the world of created goods. While possession of wealth is a kind of relationship, the Beatitudes recognise that people are more important than things, relationship with God and man more central than possession of wealth.

__________________

[1] We need the equality of opportunity to level the playing field for individuals to gain progress. We also need to be aware that equal opportunities do not guarantee equal outcome because there is such a thing as systemic inequalities. For example, children from richer families generally have better connexion. Thus, the equality of opportunity provides a measure of how equal our chances of success are whereas the equality of outcome is a measure of how successful we actually have been in making sure that the playing field is level.

[2] This is not quite true. "Au contraire", in today’s social structure, those who control the story will have the wherewithal to demonise anyone who dares to stand apart from the approved narrative. Take for example, “Blackface PM” who has no problem vilifying any lorry driver who takes part in the protest convoy as racist, misogynist and white supremacist. The PM actually belongs to an elite dynasty because his father was formerly the prime minister. Complicit in his attempt to steer the narrative is a compliant mainstream media. The challenge is how one perceives of the way events are being described is dependent on where a person stands on the political spectrum.

[3] Our idea of being the best of who is more virtual than virtuous. Being good is not as important as looking good. In other words, looks matter more than substance.

[4] In an effort to right the wrongs, that is, to remedy injustice we may miss the point that in order to alleviate inequality, we may have to remedy the other first, that is, return to trusting God. Seek first the Kingdom of Heaven and the rest will fall in line. When we are in God’s hands, we will be a blessing for others in every sense of the word. When we love God, justice will follow.

From someone who considered himself too young last Sunday, this week we land on a prophet with unclean lips. Today we continue with the theme of vocation and the spotlight seems to shine on the merits of those who have been missioned by God. Isaiah or even Paul’s sense of unworthiness stands in stark contrast to the self-absorption of our current age which is epitomised by the self-confident tagline from the L’Oréal advertisement: “I am worth it”.

Lack of self-confidence and poor self-esteem appear to be the twin scourges of modernity. Could it be that we have conflated self-worth with achievement? If you are unable to do anything, you are useless and you might as well not live. Fused into our notion of a person is the important criterion of utility. The prized individuality we seek, which we think ultimately defines us, has been hijacked, in a manner of speaking, by a need to prove or make a name for ourselves. Is it a wonder that the old and aged are apprehensive when they have outlived their usefulness? Here again, we encounter an amnesia that we are a reflexion of who God is—ours is an unmerited “imago Dei”. The image of God, not what we are capable of, is the basis for our unique individuality.

Self-worth or self-esteem are funny concepts to grapple with. Present practice is not to admonish children or employees in full view of others because we recognise that public dressing down can affect one’s future performance—akin to PTSD. There was a time when parents would pinched their children for fidgeting during Mass. Today some parents allow their children the full expression of their enthusiasm believing that unfettered freedom essential to the full flowering of their creativity and talents. This is not a criticism of parenting style but an acknowledgement that a modicum of self-confidence is needed for a person to flourish.

What is ironical is that self-esteem does not seem to be in short supply when we consider how, for a select few, the confessional is the place to proclaim and declare their sanctity. “I have not committed any sins and in fact I have been good. I do not know what sins to confess”. This is not pride and not even a lack of humility but more an expression of the loss of the true sense of self before God.

What is the difference between our “distorted” sense of “self-confidence” and these great prophets and saints’ self-abnegation? We may miss the subtle difference in our rush to embrace the mission entrusted to us by God because we are to task-focused or task-oriented. There is a mechanical or programmed quality to the way we conceive of our vocation. The notion that “there is a job to be done” fits into our pragmatic, productive and performance psyche. Contrast our calculative and control criteria with the 2nd Reading of last Sunday. Paul spoke of love. What was central to the vocation of the Prophets like Jeremiah and Isaiah, the Apostles like Peter and Paul was not their credentials, capability or competence. At the heart of their ministry was not duty but devotion indicating that everything we do must be marked by love.

Here we are not speaking of the love we are accustomed to hearing from popular music or watching romantic movies. Instead, it was love that occasioned Isaiah’s declaration of self-contempt. However, this unworthiness is less about Isaiah’s self-estimation but more a profound realisation that in God’s holiness he gasped in shame at his own poverty. So, “I am a man of unclean lips” was not self-denigration but instead, it pointed to God who should be his everything and to himself, the remorse that he has not love God enough. When our heart is bursting with love for God, we will never stand before Him feeling worthy and that is not an indication of the lack of self-esteem. Rather, it is a liberating recognition how much more one ought to love God.

Vocation in an era delineated by self-definition, meaning that one’s status or stature is established through self-manufacture, the mission of God is going to be conflated with one’s personality. Mission and personality are not mutually exclusive, in the sense that Jeremiah the prophet was shy and St Jerome was belligerent and yet one spoke and the other translated God’s word. What is damaging is when personality takes precedence over the mission. This can be noticed in the liturgy where many instances of “saying the black and doing the red” feel inadequate. For example, the introductory greeting “The grace of the Lord Jesus, the love of God and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you” sounds rather formulaic and therefore not personal enough. After this scriptural salutation, the celebrant injects a personal hello with a “Good morning” and the congregation responds with a “Good morning, Father”.

Jeremiah, Isaiah, Peter, Paul and countless saints made a name for themselves by putting God’s will first. Their singular passion flowed from their intimate relationship with God. No doubt they had a mission to accomplish and they set their hearts on it but it was always “Zeal for your house will consume me”. For them, the mission was not a task because it flowed from the love for God.

Thus, the criteria of success or achievement or competences are not measures of our love for God. It is not how much we can do that proves our love for God. Instead, an inability to sense our unworthiness could be a sign that we may have accepted performance indices as the keys to the success of our mission. Where is the love? Think of the older brother in the parable of the Prodigal Son. He did a lot for the father but it was out of resentful duty.

St Ignatius makes the connexion between love and action by asking these relevant questions.

What have I done for Christ?

What am I doing for Christ?

What will I do for Christ?

These questions may fall into the category of “doing” more than they express our love for Christ. But they are not mere questions from the perspective of “utility” or “achievement”. Rather, given that we love Jesus, then what will we do for Him, mindful that we are at the same time, unworthy. Take the example of Peter. In fishing, he was a man over-confident in his experience. In eagerness, he falters as he steps into the raging seas. In bravado, he overstated his courage to follow Jesus. In defence, he overstepped his mandate by cutting off Malthus’ ear. In Peter’s life, we begin to appreciate that mission is not just a task or burden laid on our shoulders, although in reality, it always feel like that. Instead mission is love as witnessed by Peter’s impulsive leap into the water half-dressed in order to get to the Lord whom he had come to love and would ultimately lay down his life for. It was a realisation that his desires and actions could never exhaust the love for God that he cried his own unworthiness: Leave me Lord, for I am a sinful man.

Staying on the theme of mission and merit has been good for it allows us to appreciate what should animate our vocation. The pandemic has removed the burden of duty or obligation and instead it has allowed for a possibility that our obligation flows into devotion or love. For now, in this Diocese, there remains no obligation to attend Mass. Devotion or love is why we come to Church and not duty or obligation. May this devotion lead us into a deeper passion for Jesus our Lord which allows for a fuller embrace of our vocation—to be the best of who we can be for Him, for His Church, for our country and for humanity.