From the media headlines, broadcast, electronic or print, one gets the impression that the Church is going to Hell. Do you believe this? If you do, then it follows that Christ will go to Hell too. Yes, from the looks of it, people can accept the idea that the Church will go to Hell but they balk at the idea of Christ going to Hell. [1] There is a divide between Christ and the Church. Good Shepherd Sunday, otherwise known as Vocation Sunday, may help us bridge this divide.

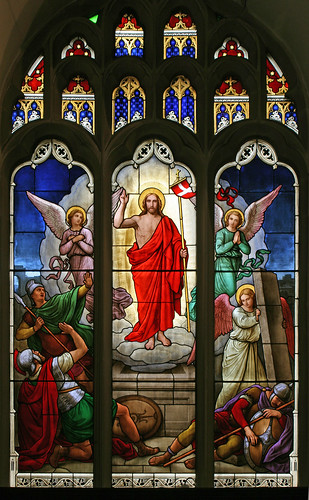

From the media headlines, broadcast, electronic or print, one gets the impression that the Church is going to Hell. Do you believe this? If you do, then it follows that Christ will go to Hell too. Yes, from the looks of it, people can accept the idea that the Church will go to Hell but they balk at the idea of Christ going to Hell. [1] There is a divide between Christ and the Church. Good Shepherd Sunday, otherwise known as Vocation Sunday, may help us bridge this divide.I begin by clarifying the statement made earlier. The Church will never go to Hell because She is forever the beautiful and faithful bride of Christ and Christ’s promise to Her is that He will be with Her until the end of time. The Exultet proclaims rightly on Easter Vigil that the Church is “radiant in the brightness of Her King”. Thus, She stands as the light to the nations.

The Church will never go to Hell BUT you may and I may. Each one of us stands a chance of going to Heaven as well as to Hell. The point is when we behave badly, we dim the light of Christ and we tarnish the beauty of the Church, our Mother. But, more than just bad behaviour, our sins disfigure Her.

You can sense that I am trying to establish the credential of the Church so that the proper question may be asked. If each one stands a chance of going to Heaven or to Hell, what is the deciding factor? The Gospel tells us that Christ, the Good Shepherd, is unlike the hired man. He will lay down His life for His sheep and He has. No sheep is ever lost by Christ who did not want to be lost. Therefore, if Christ is the Good Shepherd who is always ready to lay down His life for His sheep and if the Church is the faithful Bride of Christ, then, the deciding factor, according to the Gospel, boils down to whether or not we choose to listen to His voice and follow Him and stay with His Church. The last part of this statement is important because we tend to confuse people with the Church. To leave the Church because of priest or people is understandable but it is analogous to committing “spiritual suicide”. Christ through the Church continues to feed us with His Body and Blood. In short, Christ, through His Church, saves us.

What we face today seems unprecedented. Whilst leaving the Church is tantamount to committing spiritual suicide, some of us priests have “spiritually murdered” those who have been placed in and under our care. Through our actions—our sins—the voice of Christ through His Church is surely shaken and weakened. What can we learn from this and what ought we to do?

As a whole, the current scandals have opened our eyes to an important truth. The truth is not that we are sinful NOW as if we have just “discovered” sin. We are sinful and have always been. There is a lot to be ashamed of. But, if you let the initial feeling of embarrassment subside you will find that there is nothing of which we should be surprised with. History is a great illustrator. Through history, we learn that the Church survived Pope Alexander VI. He had many illegitimate children and he even put out hit-men on his enemies. If you want some perspective, our sins pale in comparison to his. Yet, the Church survived because of Christ’s fidelity to Her. This was proven by Napoleon’s threat to Cardinal Consalvi when he said, “I will destroy your Church”. And the Cardinal’s response was: “No you won’t. Not even we have succeeded in doing that”. He knows the strength of Christ’s promise.

Where does this knowledge bring us to? The Cardinal’s response touches each one of us personally. “Come on, give Christ and each other a break”. How? By committing fewer sins. Another way to describe this is to grow in holiness. History has shown us that whenever moral laxity creeps into the Church, soon scandals will follow. Immorality and scandal are two sides of a coin. The appropriate response to our current evil is a return to holiness. Holiness is the antidote to immorality and the cure for scandal. Our current situation is a clarion call to the Church to return to sanctity. The bridge between Christ and the Church is built upon holiness.

However, there is something more profound that we ought to ponder on. That the world is shocked by the scandals but is not as troubled by the general immorality shows how apathetic it has become. Black Eyed Peas chronicled that quite well: “What’s wrong with the world, mama? People livin' like they ain't got no mamas. I think the whole world’s addicted to the drama. Only attracted to things that'll bring you trauma”. The media’s attraction to the scandals may reveal a journalistic passion for truth as it exposes the hypocrisy of yet another untouchable institution. But, the relentless pursuit also exposes a deeper truth: a world in deep and self-consuming despair; a cynical world bent on proving to itself that nothing can be trusted. [2] It is a curse of the self-fulfilling prophecy. When we believe that we are unlovable we do all in our powers to prove that we are unlovable so much so that in the end we will say, “There you see. I am unlovable”. When we believe nothing can be trusted, then we will unconsciously search to destroy everything. [3]

In a world where being media-savvy is equated with wisdom, what should our response be? A priest warned me that I would get into trouble for speaking up. It seems that apologies are not enough. The Pope’s "sorry" was not good enough. [4] So, my response was this. Take a gun, shoot the Pope. Kill all the priests. Then ask this question: Are our problems solved? Would killing all priests make up for the lack that apologies do not supply? You know the answer. If killing is not an adequate solution, what is?

Let me make a little detour here. When the Pope issued the Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum [in English—Of the Supreme Pontiff] motu proprio [of the Pope’s own accord] he approved the celebration of the Eucharist and most of the sacraments according to the liturgy prior to the reform of 1970. The Eucharist celebrated with the Missale Romanum is now called the Extraordinary Form. According to this form, the people and the priest face a common direction: the East or ad Orientem—the direction where Christ was to come again. Sometimes this is derogatorily spoken of as the priest celebrating the Eucharist with his backside turned to the people.

What has this to do with the scandals? A good question! “Ad Orientem” directs the focus of both the priest and the people to what we are doing and to whom we are praying. When the priest faces the people, it is possible that we begin to view him as a celebrity. He becomes a performer and with him, we are subtly drawn into a cult of personality. The cult of personality feeds on the "Gospel" of Nice and according to this Gospel, the priest is often reduced to his functions. He is nice because he can do this or that. He is nice because he is friendly and cool. But, much as I personally like it, this is not what the Church has in mind. If you think about it, if we glorify the cult of personality or celebrity, should not our lives be tainted with scandals? This should not surprise us because a celebrity becomes more famous because of scandals. The more sordid the life of the celebrity is, the more famous he or she becomes. So, let us enter further into another reflexion.

The scandal of the priesthood is not really the abuse scandal. It is far deeper than that. Here, I want to be clear that this is not an attempt to trivialise the injustice suffered or the pains inflicted. Neither am I advocating that we hush them up. The scandal is rather the claim that the priest is Alter Christus—another Christ. It is a scandal because in the face of what is happening, the Church still dares to claim Her priests to be such. Alter Christus is NOT friendly according to the model of the Gospel of Nice, which is what the world likes. Instead, Alter Christus means 3 things—first, the priest is servant of the Word. Therefore, he must stand ready to be mocked and laughed at like Christ was. Second, he is servant of the Sacraments. This means he is the servant of the sacred. He gives God’s holy people God's holy gifts—the 7 Sacraments; he is a channel of God's holiness. Thus, he is to be holy. Thirdly, he is servant of authority. The exercise of authority is a service. Current model of authority is to be at the top and lording it over others. But in Christ, authority is service as we witnessed on Maundy Thursday where he washed the feet of the 12 men.

Let me tell you a story of what an Alter Christus is like. This was told to me by another priest. It concerns Father A and it took place during Holy Week. Father A has been debilitated through stroke and as far as his liturgical functions go, he is pretty much useless. As there was a shortage of priests, Father A was sent to “supply” for a chapel. When the parish priest visited the chapel, he asked how Holy Week went, one of the parishioners said, "Thank you Father, thank you, for sending Father A. We saw Christ in him".

Ad Orientem and Alter Christus open our vision to another world. Perhaps you will begin to realise that the deeper scandal is that the Church, through useless men, dares to propose a vision of a world that is shot through with the presence of God. The scandals expose not only the sinfulness of priests but really a desperate world toying with the atheistic idea of whether or not there is such a thing as God; just like the Cross—a stumbling block to the Jews and a folly to the Gentiles. The divide between the Church and Christ is really a divide between the profane and the sacred; a divide between this world and the next world. Alter Christus and ad Orientem are both pointers to the presence of God and that our worship and sacrifice are directed to Him.

The end result of a personality cult is that the priest becomes more “human” [more like us] so that we can identify with him instead of we becoming like “him”, who is more like Christ. Today, it is frightening to be a priest. But it is also a challenge. According to Fulton Sheen, even a dead body can float downstream. It is easy to be a Catholic when everything is well and good. What is more courageous is to stand against the current. To bridge the seeming divide between Christ and the Church, priests must become more like Christ. Thus, the model of the celebrity-priest based on the cult of personality must now give way to a priest whose life is nothing but a mirror of Christ—like Fr A was. A priest is “another Christ” teaching us to face God the Father. The more he is like Christ, the more human he becomes. Not the other way around.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] If you think about it, the Church might as well be in Hell. The whole furore surrounding the Pope’s visit to the United Kingdom does not just reflect a prejudiced and illiberal attitude towards the Catholic Church. It could also mean an understanding there is nothing divine that can be discerned in the Church. Thus, liberation is not found in organised religion. Instead it is left to the individual’s faith to find the way to Heaven. Being in religion could endanger one’s soul.

[2] In a sense this is nothing new. It is the old heresy of Gnosticism born anew in a hermeneutics of suspicion. Gnosticism denies the possibility of the Incarnation. The Incarnation can never take place because “matter is evil”. If we accept this thesis, then the “Sacraments” are not possible because they are premised on the possibility of the Incarnation taking place. Thus, the Church as the Sacrament of Christ is not possible. The Church is the only institution that unabashedly claims to be divine. Is there anything divine at all in our sad world?

[3] This cannot be helped if you look at it. “Establishments” so necessary for the organisation of common life have consistently failed us—political and economic institutions, governments and the financial establishments—beginning with Enron, followed by Bear Stearn, Lehman Brothers and the likes. From these, it does not take much to extend this mindset to the Church. Of course, the Church does have her share of sinful men. The difference which the present mindset has with the Church is this: She is both divinely instituted and humanly constituted.

[4] It is not easy to draw the line between the demands of justice and the rage of revenge. When our “justice” is fuelled by revenge, no apology is ever enough.